The Polish Resettlement Corp

Poland’s connections with Scotland reach back centuries, with links largely based on trade, security, cross-migration, education and labour. Inter-marriage is fairly commonplace, and Bonnie Prince Charlie was half-Polish on his mother’s side. During WWII and its aftermath, those links were further strengthened as many Poles moved to Scotland.

Poland had alternated historically between having its own monarchy and being occupied by foreign powers. After WWI, Poland regained its independence under the Treaty of Versailles, only to be invaded again twenty years later, this time by Germany and then Russia in 1939. In 1940, after Poland fell to the Nazis, what remained of the Polish army was evacuated, with many soldiers sent to Scotland by the Polish government, which was itself in exile, first in France, and then London.

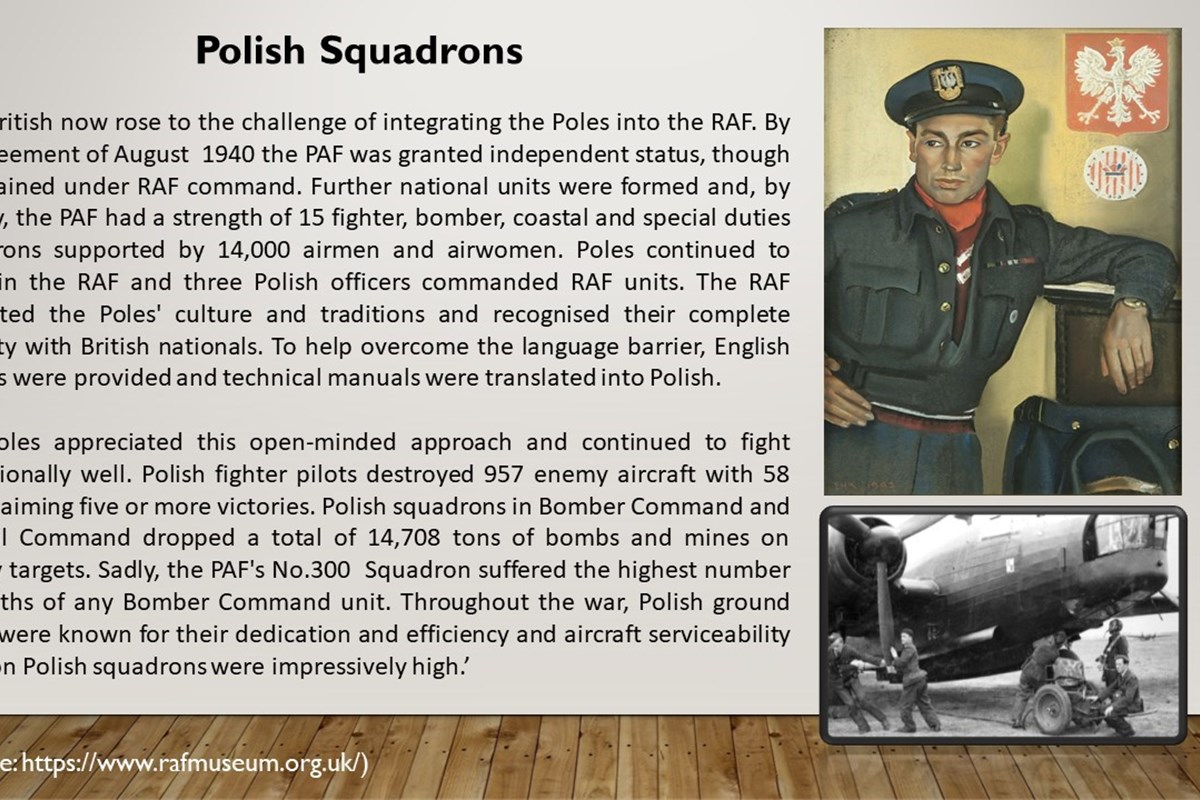

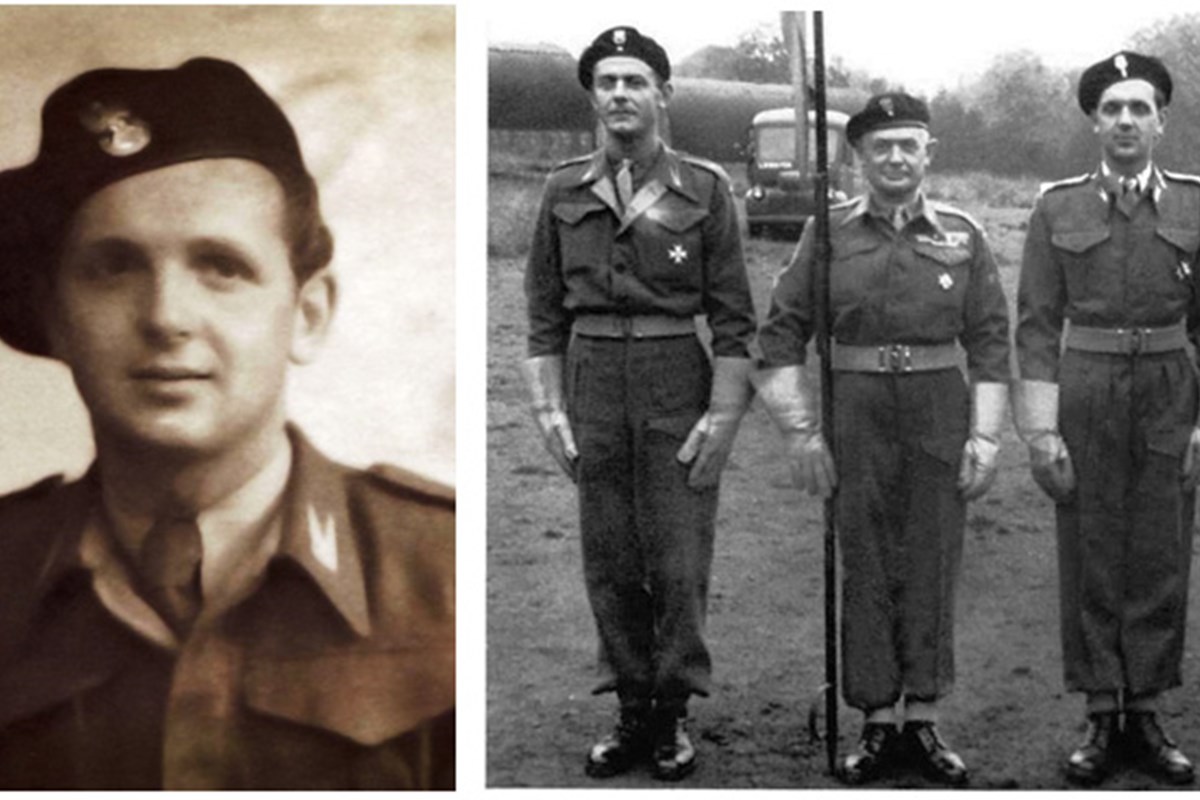

The Polish army, air force and navy made huge contributions to the allied war effort, particularly the British campaigns. The following are only a few examples of their many achievements and sacrifices during World War II. The 1st Polish Armoured Division landed in France in August 1944 and joined the Canadians to help close the Falaise Gap. The Polish air force was prodigious in their contribution during the Battle of Britain. The Polish Navy took part in the Normandy landings and escorted Atlantic convoys of ships. A great number of Polish soldiers ended up in Scotland, initially in camps in Biggar, Douglas and Crawford. Men and women (the great majority were men) who were of age were formed into military units and were stationed all over Scotland. Carry out work such as guarding in POW camps and making sea defences on the east coast of Scotland against possible Nazi invasion from Norway. Their numbers were added to, over time, by soldiers released from Soviet captivity and other members of the Polish diaspora.

The soldiers and other combatants from Poland mostly found a good welcome in Scotland and Britain generally, due to their anti-German stance. Crowds cheered them as they marched up Sauchiehall street in Glasgow. The Poles often involved themselves in sporting and artistic activities, involving the local communities where they were stationed, perhaps most notably in Fraserburgh and Arbroath.

After the war, Stalin imposed a communist government on Poland, reneging on his promise at the Yalta Conference in February 1945 and in meetings which followed. The Polish Government in Exile was formally not recognised by the British Government from the 6th of July 1945. This was a seen as a huge betrayal of the Polish forces and was named ‘The Western Betrayal’. Most of the Polish forces in Britain were loyal to the Polish Government in Exile and did not want to return to a Poland under communism. Many were caught in a terrible dilemma between staying in Britain and going home, as they had wives and families back in their homeland. Persecutions were being carried out in communist Poland of soldiers who had fought for the allies.

The British Government agreed to the Poles staying in Britain, if they wanted to, in March 1946, after Prime Minister Clement Atlee had initially tried to encourage them to go back to Poland under the belief that they would be welcomed home. The government were undeniably under pressure to extend a welcome to the Poles due to what was viewed as a betrayal of both the British reasons for entering the war, and of the Polish troops who had served them loyally.

The Polish Resettlement Corp was announced by Aneurin Bevin, the Minister for Health, in May 1946, and began recruiting in September that year. The Polish Resettlement Act came into force in 1947 and was the largest ever immigration programme carried out by the British Government, with over 200,000 Polish men and women, and eventually their families, being welcomed into Britain. A minority of Poles refused to join the PRC, viewing it a betrayal of the Polish constitution and the end of the hope that communism under Stalin would quickly fall.

People joined The Polish Resettlement Corps on a voluntary basis and could leave at any time to take up work or emigrate. The aim was to prepare Polish people for British life, with English lessons and work experience and training. The Poles often trained in trades and some undertook professional training. The members of the corps came under British military rule and were entitled to army pay and unemployment benefits. However, there were some barriers to the Poles working in Britain, including opposition from trade unions who saw them as traitors to the left for fleeing communism. Many politicians and newspapers of the time spoke out against this. The trade union opposition to the Poles mainly dissipated as it became known how extreme and brutal the Stalinist regime was.

The Polish Resettlement Corps usually moved into former military bases and hospitals, or POW camps, like Patterton Camp. There were also family camps, where ex-soldiers could be accommodated with their families who had arrived from Poland.

We know very little about the PRC at Patterton, other than that they arrived after the Germans had left in the summer of 1947 and they stayed until the disbandment of the PRC unit in the spring of 1948. Some of the PRCs may have stayed longer and become part of the residential group – more on that later. One source describes them sharing the camp with people living there as a result of the post-war housing crisis. None of our respondents who were in the camp post-war remember the Poles, but then, they were children at the time and the Poles were only there for a short period. However, many people remember Polish people living in and around Patterton in the immediate post-war years and later. A couple of our respondents have memories of Polish people in the area but do not know if they were in the PRC:

Not at the camp. Only the ones that were moved up here eventually. We’d a few just living round this area. Along the road.

Norma Wilson

And the Poles…my brother seems to remember, whether this is relevant or not, that we had one of the Poles visit us at our house, but I have no recollection of that whatsoever.

Alan Flower

Nearby camps also housed some Poles, including Johnstone Castle Camp, where they constructed a chapel, and Stewarton Camp, which was for Poles who wished to return to Poland in due course.

How would members of the Polish Resettlement Corps at Patterton have felt during their stay? Many would have been worried about family members back home. There were various prejudices against the Polish in Scotland, as there were in other parts of Britain, which may have affected them. Ingrained sectarianism in certain parts of the country resulted in bad feeling towards the mainly Catholic Poles. Indeed, the Free Presbyterians in Dingwall and Tain protested the formation of the PRC, believing it was a Catholic plot to infiltrate the country; they were also fearful that the high unemployment rate in the Scottish Highlands at that time might be exacerbated. There were also those that believed that Poles committed a disproportionate amount of crime. There were incidents when these prejudices and fears came to the fore, such as in Caithness, where locals expressed their fears that there was something criminal with Polish people sending food parcels back to their relatives. Their fears were unfounded.

It has to be said that some Scottish men were threatened by the politeness and charm of their Polish counterparts. We have heard from the daughter of a former member of the PRC that her late father kissed a lady’s hand on their first meeting and it always went down well with the lady in question, though some men were overtly unimpressed by this practice Nonetheless, over 2500 marriages occurred between Poles and Scots after WWII.

Equally, there are many reports of kind treatment from the local population. Bonds formed with the Poles during the war over sports and entertainment would not easily be forgotten. Many people would also remember their contribution during the war. One ex-member of the PRC said that people generally could not do enough to help him but, of course, it depended on the person. The Ukrainian community in Scotland, who perhaps would have encountered the Poles in mining towns, were said to be very supportive of them.

The Polish Resettlement Corps were disbanded in 1949. By the 1951 census there were 10,613 Polish born people in Scotland. The vast majority were men. Many Polish people had emigrated to America, Canada and Australia, amongst other places. Polish societies and institutions were set up to support the Polish people in Scotland and to prevent Polish culture from being lost. Polish shops and restaurants opened. Many Poles kept their traditions going and sent their children to Polish school at the weekend; others did not. Nonetheless, members of the Polish Resettlement Corp formed the basis for much of the Polish community in Scotland and the UK today.